The first record of the land’s ownership is associated with a man named Thomas Clingman. The Clingman name, although I was never taught anything about the man himself, is associated with all sorts of places in Asheville: the Clingmans dome (sic, the apostrophe has presumably been ellided by time), the clingman cafe, the clingman lofts, (where my friend-from-middle school’s dad lived) etc. Clingman was a North Carolinian politician in the 19th century, which is really all you need to know about his politics. Seeing him in his thin wool suit in black and white is strange, because I’ve always associated the name Clingman with hiking and rock-climbing. Clingman doesn’t look very athletic at all, he just looks wealthy.

Did Thomas Clingman hike through the same canopy of laurel bushes that my dad and I did? Did he place it among the landmarks of the mountain, same as the small boulder that marks the top of one of the ridges about a third of the way up the mountain? If not, did he allow others to hike, establishing those first trails up the side to the top? Or, perhaps, during the time he owned it, it was totally deserted, or used only for occasional hunting.

Did Clingman really own this mountain? Can you really even own land at all? Let alone a mountain? I say this with the same slightly self-effacing tone of mystique that a horse girl might use when saying “Can anyone really ever own a horse?” A cliche, and a non-question, but also an important point about what land ever is. No one ever owned mount Elseetoss. (I don’t know that for sure, but, given the contrast between western land use practices and Indigenous land use practices, I can fairly confidently guess that no one individual ever looked at the mountain and said “I am the sole owner of that peak, the dirt, the stone, every tree along its sloping mass, every single one of the scurrying creatures in its caves and crenulations, the wind that passes through it in the summer and the view that spans for miles from it in the winter,” because that would be ridiculous.)

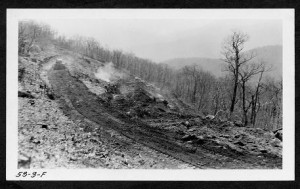

But Clingman did own Mount Pisgah, inasmuch as the colonists’ law allowed. (If I were Christian here, I might talk about how man’s earthly laws attempt to supplant the heavenly law of the divine, but I am not Christian.) To own land in the way that the settlers did, and the way that we still do, is to use it to the point of abuse. The view that one is, as an individual, the sole arbiter of what they do with the plot of land they stand on is a categorically harmful view. It ignores the fact that the land is connected, both in time and in space. The earth will feel the effects of misguided land-use for centuries, if not longer, and those effects will permeate not just to surrounding plots of land, but also deep below, and miles out in the watershed, and out to sea. As Wendell Berry said, “Whenever greedy or thoughtless men have lived on [the hill, it] has literally flowed out of their tracks into the bottom of the sea.”