Sitting in the garden, listening. It is a bright, but shady mid afternoon. The sun is warm.

My roommate and I walked down the trail to a hidden bench behind some shrubs. The light was shining through the trees just enough to be a pleasant energy.

I picked a flower from a near by bush- it’s pink but not to bright, just like a flamingo. My roommate tells me it’s a hibiscus.

We are sitting by a bench as a lay a blanket down and try to sit in silence or as much silence one can have in the city.

There is a slight breeze. Being in nature in Greensboro is different than being back home in the country.

I love the city because it’s always moving, but also my love for the country is unmatched because of the immediate ease it brings me.

Movement. Memories. Music. Meditate. Magnetic. Mindful.

Being out in nature clears your head and makes you think, but not regular thinking, more wondering.

BE still. I tell myself. Repeat. Breathe.

I am a very energetic person. Being still is a challenge for me. Going outside and sitting down and listening helps me. I also try to soak up as much information as I can.

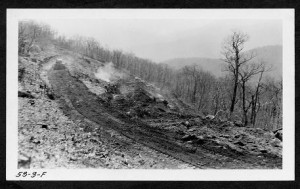

Being in nature in Greensboro is different than being back home in the country. City nature is always moving and has lots of energy. Country nature is slow paced and quiet. In WV, It is quiet. Walking down the boat ramp to the nearby river it is silent.

Small town, country nature isn’t man made either. it is authentic and effortlessly wonderful.

However, walking in the city is there is always noise. The city has nature in its own way. A lot of trees and flowers. There is no silence, there is always noise.

In the city you have to be appreciate of the nature thats there, even if its manmade. Acknowledging it is important, but nature also needs to be preserved.

It hurts going home and seeing development happened where farm fields used to grow crops for acres and acres. Every time I go home, I see something new being built. In the city it is already built, but coming from a small town it’s still considered big to me.

Walking through the bicentennial, there is a wildflower section. On the path there is a picture stand with information about all the wildflowers that can be scene. The wildflower path is my favorite because it reminds me of my mother. I have wildflowers tattooed on me for her. Whenever I see wildflowers I think of my mother and it instantly changes my mood and makes me feel a type of way.

The dandelion, ox-eye daisy, queen annes lace, and chicory are some of the most common wildflowers in North Carolina, and are very important to ecosystems.